|

<< -- 3 -- Roderic Dunnett UNALLOYED GENIUS

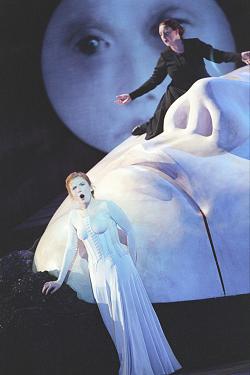

By contrast the women -- Euryanthe in pure (and in Act III, helped by

Jennifer Tipton's lighting, sullied) white, Lauren Flanagan's

spidery Eglantine (not, I felt, as well sung or convincingly acted as some

opined) in aggressive, spidery black, each lend the scene some 'colour',

or at least, definition. Much of Macfarlane's splendid, consciously

solid, dourly pastel sets -- a series of beige-grey-brown spikes (spiky trees,

spiky spears, spiky knives, shaped and coloured like soily icicles), beige

chairs, beige tables, beige rooms, plus thick walls, heavy objects, sturdy

bodies) -- maintained, powerfully, this forbidding feel; big blocks, like

the brains of the apparently mindless, almost Neanderthal militaristic society

that peoples them; so does Macfarlane's one splurge of backdrop colour :

a starry dark blue sky with what seems to be a weeping, or at least dewy-eyed,

moon.

This grieving moon-face is no casual decoration. It is a face with a

function, for possibly Jones and MacFarlane's most striking coinceit

of this riveting evening was the tomb of 'Emma' -- Adolar's suicide

sister, presumably a teenager like Euryanthe : a massive 'shape'

of alabastrine white block, in the shape of an elephantine 'beached'

human face. Not only is Macfarlane's moon-face, wanly gazing down,

a mirror of this, wrenched from the massively three-dimensional into an

almost Jugenstil two-dimensional vertical. It has the crucial effect of

putting the Emma story -- purportedly the central problem in Helmina

von Chezy's linguistically challenged libretto -- right at the heart

of the opera.

Anne Schwanewilms as Euryanthe with Lauren Flanagan (above) as the evil Eglantine in the Richard Jones - Mark Elder Glyndebourne 'Euryanthe'. Photo: Mike Hoban

|

Euryanthe, Eglantine and later, even Lysiart climb all over this ominous

block, visually immersing themselves, almost caking themselves, in it. A

brilliant stroke; for the problem (pace received opinion) is categorically

not the Emma saga's ineptness (how easily Wagner might have

served up something similar; in a sense The Flying Dutchman unlocks

something similar); or its gratuity (it isn't, it's central);

rather, the Emma explanation is psychologically astute. But the way

it is often seen as something to be played down often renders it, in production,

superfluous, tiresome, and embarrassing.

Weber, however, goes for it hell-for-leather, allocating some of his

most evocative music to this scene: it's not as if he thought

it weak.

Continue >>

Copyright © 28 July 2002

Roderic Dunnett, Coventry, UK

RODERIC DUNNETT ON THE RESIGNATION OF NICHOLAS PAYNE

GLYNDEBOURNE FESTIVAL AND GLYNDEBOURNE TOURING OPERA WEBSITE

RODERIC DUNNETT ON THE RESIGNATION OF NICHOLAS PAYNE

GLYNDEBOURNE FESTIVAL AND GLYNDEBOURNE TOURING OPERA WEBSITE

|