|

ALICE McVEIGH reviews

ALICE McVEIGH reviews

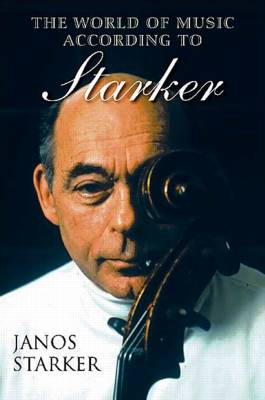

'The World of Music According to Starker'

And now, as long threatened/promised, my review of eminent cellist Janos Starker's memoir The World of Music According to Starker.

And here I must declare an interest, which is that I knew Starker pretty well, and indeed studied with him around 10 times, though he was so rarely around that I studied a good deal more with the superbly gifted Gary Hoffman, his assistant in those far-off days in Bloomington, Indiana University School of Music, graduation class of 1980.

And he taught me a lot.

He taught me that the music profession was full of pain ('If you think that I am nasty, wait until you go into the world of orchestras!')

He taught me that masterclasses can be so revolting that I still feel hot with shame that I didn't get up and walk out.

(Starker to a pretty little cellist who was admittedly not brilliant: 'You will never make it. Go and have children.')

He taught me that he could play anything, without the music, without missing a note.

He taught me that reading was dangerous.

(I rashly quoted the philosopher Kierkgaard to him, upon which he said, 'What, you read Kierkgaard? For a cellist, such reading is dangerous.'

'Why is it dangerous?' I wanted to know, being in a deeply, rashly, philosophical phase of my adolescent life. And he said, 'Because it drowns out the music!')

I'll never forget the time he said to me, coldly, and with the clipped precision for which he was famous, that I would never get anywhere in the profession because I got the bow shakes. 'To lose 5% of one's technique is normal,' he told me, 'and 10% is not uncommon. But you lose 15-20% of what you could do when you perform! No one could afford this!'

Yet how was he to know, back in 1979, that, thanks to the wonders of modern medicine, beta blockers would be born?????

Yet he was right, according to his lights, and, I'm sure, were we to meet again (which is impossible, as I don't want to) that he would point out that I only ever got to play repeatedly with Sir John Eliot Gardiner and the BBC Symphony and the Royal Philharmonic thanks to these little pink pills. (And he would be bloody well right!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!)

Anyway, where was I? Yes, so I cannot claim to approach this book with unmixed feelings. Starker plays the cello like an angel, but without the least spirituality. No true cellist can approach him except with awe, yet there is something so lacking in his Brahms as to suggest emotional dyslexia. I have probably never met anyone with such an immediate and irresistably sexual presence, yet his book is so clinical and so stark that he might not know the meaning of the phrase. And, saddest of all, this genius, this cellistic superstar, not content with the unusual and unparallelled gift he was given, fancies that he can write, which he can't. He favours us in the memoir with several short stories, each more clunkily written than the last, and each starring a character who seems to be (no less) Janos Starker. The actual prose of the memoir is more than acceptable, though with the usual grammatical mistakes of using disinterest to mean uninterest and so on. Yet these stories would be taken apart, unmercifully, by any decent writing circle worthy of the name.

The two most interesting parts of the book are the first third and the 'Organised Method of String Playing' at the end.

The description of the young and powerfully determined young Starker is profoundly moving. Here he brushes shoulders with history, with small town Hungary and the tribulations of a young and (then unfamous) young soloist-in-waiting, with his work in munitions factories and anti-semitism, of being talent-spotted by Dorati and not taking good-enough (as youthful principal of the Metropolitan Opera) as an answer. I could almost, once again, hear his dry, 'My Russian colleague,' references to Rostropovich here, as he fought to win the place that his own genius deserved, and that his 'Russian colleague' found (in some ways) so much more easily.

The book gets dull once he's a major soloist and enjoys himself poking fun at conditions of music-making in African countries etc but picks up no end when he lets fly on technique. I have always defended Starker's musicality (unlike so many players, he puts the composer's preferences first) but even his greatest critic cannot deny that his technique is probably the best that has ever been. Starker, in short, is to the cello what Heifitz is to the violin. The reasons for this are succinctly advanced in his 'Organised Method of String Playing,' here (I also have the book of exercises) in which he puts his theories down for all of us lesser cellistic mortals to behold. I defy any thinking cellist to read this without the shock of recognising he is, at last, in the hands of the master. Starker's understanding of how cellos work quite simply begins where mine leaves off, and it's very small consolation to me that I write the better ... I intend to make all of my serious pupils imbibe this chapter whole, with inestimable impact upon their bow-arms and left-hand techniques. The boy has, here, quite simply written the book on cello playing: and all in a mere 25 pages.

Buy it. Read it. Apply it.

(God, I sound like him again already!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!)

Cordially

Alice

Copyright © 8 April 2005

Alice McVeigh, USA

|