|

THE PHILOSOPHY OF ABSENCE

JENNIFER PAULL investigates

four releases of Cage's Number Pieces

Never forget that only a dead fish swims with the stream. -- Malcolm Muggeridge (1903-1990), English author and journalist, senior editor of the British satirical magazine Punch (1953-57)

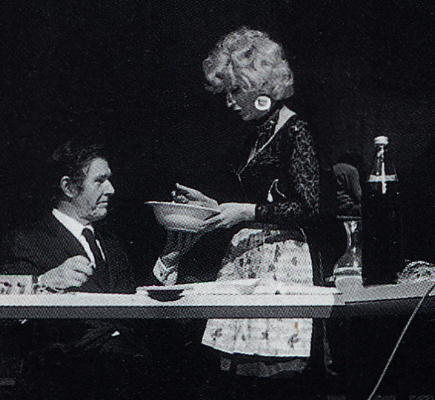

John Cage and Cathy Berberian during the first performance (1970) of part of 'Song Books' (Ninety Solos for Voice). Cathy asks Cage (seated on stage) to sample the spaghetti she has just cooked before carrying it to the audience. Photo © Philippe Gras, courtesy of Cristina Berio: taken from Jennifer Paull's book 'Cathy Berberian and Music's Muses'

|

John Cage represents a way of being; a freedom of the thought processes: a melding and discarding of all preconceived ideas about where one art begins and another continues. Cuisine, too, is definitely an art form. To think of Cage as a 'composer' is to discard who and what he was: a philosopher whose message was not the argument of words, but the contention for sound and non-sound (silence), space, time and imagination. I have referred to him previously as a sound sculptor (in Uncaged John).

Mercier (Merce) Philip Cunningham (1919-26 July 2009) has been the third great dancer to die so far this year -- Michael Jackson (1959-25 June 2009) and Pina Bausch (1940-30 June 2009) were also revolutionary in their own very different ways. Cunningham had worked with Cage since 1942, and like Cage was at the forefront of the avant garde movement in the United States for decades. He collaborated with many great artists from diverse disciplines. I was spellbound when I watched his choreography of Cage's abstract sound creations, many years ago, in the realty of the carvings of ancient Persepolis. Like Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears, Cage and Cunningham each understood the work of their partner completely.

The artist Robert Rauschenberg is to art (painting, photography, etc) what Cunningham was to dance and choreography and Cage was to music and sound. Born Milton Ernst Rauschenberg (1925-12 May 2008), he was another US member of the group that became well known in the fifties' transition from Abstract Expressionism to Pop Art.

In 1966 (with Billy Klüve), Rauschenberg officially launched Experiments in Art and Technology (EAT), a non-profit organisation, the aim of which was to promote collaboration between artists and engineers. His work also included significant contributions to printmaking and Performance Art. This was the period when Musique Concrète and Berio/Maderna's Studio di fonologia musicale had been reaching unscaled heights of experimentation in Milan.

Cathy Berberian and John Cage inside the studio. Photo courtesy of Cristina Berio

|

At the onset of the fifties, Rauschenberg had developed his 'White Paintings'. The monochromatic painting tradition reduces painting to its very essence leading to the possibility of pure experience. This is an exact parallel to John Cage's musical philosophy.

As with Cage's silent work (4'33"), the canvasses appear blank. Cage saw Rauschenberger's not as destructive reductions of art, but as hypersensitive screens he described as airports of the lights, shadows and particles. Before them, just as in front of his silent piano in 4'33", the smallest changes of light (or ambient sound) and atmosphere are captured on their surface (or by the ear of the listener).

... along with long time friends [including] the late conceptual composer John Cage, Rauschenberg pretty much defined the technical and philosophic art landscape and its offshoots after Abstract Expressionism. -- Marlena Donohue (28 November 1997), Rauschenberg's Signature on the Century on Rauschenberg's career retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum (Christian Science Monitor).

Not surprisingly, all three, Cage, Cunningham and Rauschenberg, studied at Black Mountain College. This was the first US experimental college to extol extensive work in the creative arts with interdisciplinary academic study. The first multimedia happening took place there in 1952, staged by John Cage and including all three (and others). In Black Mountain College the study of Art was seen as essential, even the kingpin of all education in the liberal arts.

To quote Cathy Berberian, a great friend of Cage and an artist much admired by Merce Cunningham:

There is no division between the Arts; they are one energy. (see High Jinx and Haute Couture).

'Cage Four 4'. © 2000 OgreOgress Productions

|

The first CD is a lacework of textured sound and silence. To quote the cover note by Rob Haskins:

In order to keep up the demand for new pieces, Cage turned once more to his long-time assistant Andrew Culver, who developed new software that enabled Cage to write music very quickly.

'John Cage: One4, Four, Twenty-Nine'. © 2002 OgreOgress Productions

|

Listen -- Cage: One 4

('cage one4 four twenty-nine' track 1, 0:00-1:44) © 2002 OgreOgress Productions

Cited on the inside of the second CD is the following graphic quotation. One of his experimental texts, this is a mesostic: a genre of his naming having progressed from Jackson Mac Low's diastics. Unlike acrostic writing, it is not the first letter of the word that is intended be read vertically:

From John Cage: 'Composition in Retrospect' (Cambridge: Exact Change, 1993)

|

Listen -- Cage: Four (Version C)

('cage one4 four twenty-nine' track 4, 1:30-2:03) © 2002 OgreOgress Productions

Cage's number pieces are a genre. Haskins writes:

One quality that unites all of these pieces is their amazing emphasis on ordinary life -- all that performers need to have is devotion both to the act of producing a sound and to hearing the sounds around them ...

The exuberance for everyday life and for discovery is at the very heart of Cage's artistic legacy.

These performers are totally dedicated. One feels their appreciation for their master and their tireless enthusiasm for the understanding of his oeuvre. I applaud their devotion and their comprehension of this mystical, hypnotising man and his vision.

!['John Cage: One<sup>7</sup>, [from One<sup>7</sup>], One<sup>8</sup>'. © 2001 OgreOgress Productions](cagecd3.jpg)

'John Cage: One7, [from One7], One8'. © 2001 OgreOgress Productions

|

The third CD contains a typical Cageism inside its cover.

There is a beautiful statement in my opinion by Marcel Duchamp: 'to reach the impossibility of transferring from one like object to another the memory imprint.' And he expressed that as a goal. That means from his visual point of view, to look at a Coca-Cola bottle without the feeling that you've ever seen one before, as though you were looking at it for the very first time. That's what I'd like to find with sounds -- to play them and hear them as if you've never heard them before.

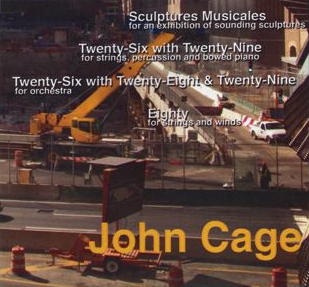

The last of the recordings to which I have been listening is the only one to contain one work with a title in words not pertaining to numbers: Sculptures Musicales.

'John Cage: Sculptures Musicales for an exhibition of sounding sculptures; Twenty-Six with Twenty-Nine for strings, percussion and bowed piano; Twenty-Six with Twenty-Eight and Twenty-Nine for orchestra; Eighty for strings and winds'. © 2008 OgreOgress Productions

|

This is a DVD (without vision). Its cover is an industrial cityscape with traffic and a crane. Inside is another Cage quote:

There are two things that don't have to mean anything, one is music and the other is laughter ... don't have to mean anything, that is, in order to give us very deep pleasure.

We don't see much difference between time and space. We don't know where one begins and the other stops ... Marcel Duchamp for instance began thinking of time. I mean thinking of music, as being not a time art but a space art and he made a piece called 'Sculptures Musicales' which means different sounds coming from different places and lasting, producing a sculpture which is sonorous and which remains.

People expect listening to be more than listening ... whereas I love sounds just as they are and I have no need for them to be anything more than what they are.

Silence, almost everywhere in the world now is traffic.

Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) was the French artist whose works were most associated with Dadaism and Surrealism. His influence after World War II was considerable in all Western art and the pluri-discipline mosaic of avant garde movements within. It is not a coincidence that Cage mentions laughter in his writings. Duchamp (Cage's chess partner) had much wit. He challenged the conventional approach to art. One of his works, a urinal he dubbed 'Fountain' was as much of a cataclysmic débacle as Cage's 4'33".

The night before I wrote this piece was the August night of the meteorite shower (13 August 2009). I sat on my terrace and looked into the infinity of space and waited. Neither the heavens nor John Cage, to which I was listening, disappointed me. He died on 12 August 1992. It seemed a fitting requiem.

These four recordings are almost impossible to illustrate in short sound clips. One cannot show how silence is framed, just as one cannot illustrate the random factor. Like the Milky Way, they appear in another dimension across which one must travel, with time, to appreciate.

To those confused and perplexed in their effort to understand the works of Cage my advice is simple -- don't. The building bricks of pure sound are as exciting, thought provoking and beautiful, as was the DNA molecule when finally revealed in its double helix (also in the early 1950s). OgreOgress Productions is an unique and dedicated nucleus of total commitment to its cause in bringing Cage's philosophy to life. There isn't one dead fish in sight. These musicians swim against the tide with perseverance for which I applaud their devotion and ardour.

I would advise my young colleagues, the composers of symphonies, to drop in sometimes at the kindergarten, too. It is there that it is decided whether there will be anybody to understand their works in twenty years' time. -- Zoltan Kodaly (1882-1967), Hungarian composer, educator, ethnomusicologist, linguist, author and philosopher

Copyright © 26 August 2009 Jennifer I Paull,

Vouvry, Switzerland

|