|

REMEMBERING HOFFY

ALICE McVEIGH writes about

cello teacher Robert Hofmekler

6 December was Hoffy's birthday. Had he lived, he would now be nearly a-hundred-and-ten. He was already in his sixties in the early 1970s, when I, his new cello pupil, a hugely nervous twelve-year-old, showed up, having been learning the cello for a grand total of about three months.

Reuben Hofmekler (1905-1994), originally from Vilna, Lithuania, already looked older than he really was. (In America, he took the first name Robert, though everybody called him Hoffy.) Almost entirely bald, despite having once sported those blonde locks which had deceived Hitler's ghoulish minions into wrongly believing him not to be Jewish, he boasted a prominent nose, a prominent paunch, irresistibly laughing eyes, a wonderful hand-span for the cello and a vaguely professorial look. His alert mind (and inner fury) had taken him straight from escaping the Nazis — all but one of all the rest of his family died in the concentration camps — into US Army intelligence, where he was, of course, signed to secrecy.

After the dust had settled he married an American and settled in northern Virginia, to become The Cello Teacher (excluding those players in the National Symphony Orchestra who taught on the side). His remaining brother Michael was more of a performer. Hoffy told me once that his cousin also escaped, and became principal cello in the Israel Philharmonic.

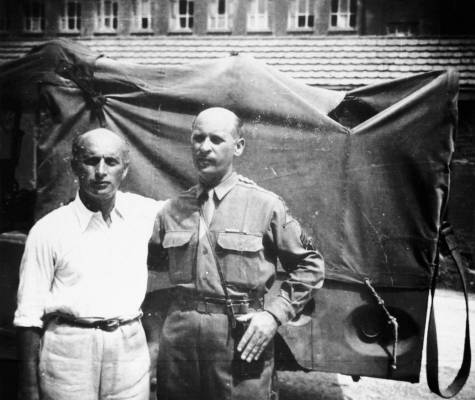

Michael and Robert Hofmekler (right) in June 1945 at Sankt Ottilien, Bavaria, Germany, on the day that Robert found Michael at the displaced persons camp at the end of World War II. Photo courtesy of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum / Robert W Hofmekler

|

Hoffy, who never lost his heavy Baltic accent, was born to teach. In his immaculate basement, beautifully decorated and always vaguely smelling of waxed furniture and expensive cello polish, he admitted scores of students into the great cello mystery. From his immaculately kept music folders he had not only the usual studies but a huge number of exercises of his own devising, hand-written in a thick, heavy but always precisely legible musical hand. Before World War II he had studied with the famous cellist Julius Klengel — an honour he shared with my last teacher, William Pleeth — so of course there were innumerable Klengel exercises, but also unending scales and exercises in double-stops and millions of admonishments to practice, advice — unlike most advice in my life — I took to heart, beginning with around three hours a day and working inexorably upwards.

Of course I was, at that point in my life, cello-obsessed. When I couldn't 'get' up-bow staccato in one lesson I burst into tears. Hoffy was sympathetic but philosophical. He said, 'You care too much. It veel get better, you will see. There are harder things in life than up-bow staccato.' (Which of course there were, and are, but remember, I was young and stupid.)

On the other hand, Hoffy was ferocious about intonation. When I began studying with him he would actually slap my hand with a ruler if I was out of tune. (This isn't a method I've ever attempted with my own pupils, as I've never been sued, and would prefer to keep it that way!) His view of poor intonation and those who permitted it is not to be told. He also taught me to vibrate on the cello long before I was really out of cello-nappies, insisting, 'A cellist vithout vibrato is like a feeesh veesout vater!'

In the 1970s, International Music Editions (despite being pretty lousy editions by today's standards) was my hero. The thrill of coming home from school and finding a delivery of new cello music waiting for me!!!!! How I rushed upstairs to try it out, how I attempted to win Hoffy's scepticism over to such (completely non-)masterpieces as the only Tartini concerto International ever published — to his utter mystification. ('Iss not the Schumann concerto good enough for you?')

Now I almost certainly wasn't 'up' to the Schumann concerto at the time, but yet another wonderful thing about Hoffy was his immense tolerance. He never once told me, 'This is too hard for you.' (Or: 'Zees ees too hard for you.') Instead, flicking amusedly through my latest waste of my pocket money he'd say, 'Thees vill keep you off the streets, pumpkin!' When I played exceptionally well, he'd say, 'Now you're playing like a little Jew'.

As already mentioned, I had started to learn the cello very late for a serious cellist, and I felt as if I was always rushing to catch up. I bought the Dvořák concerto before I was really beyond basic thumb-position and practiced all the bars I could manage incessantly. (The Dvořák will always have a special place in my heart, as it featured on one of my father's favourite records throughout my childhood in the Far East. In short, mostly thanks to my father and to the Dvořák cello concerto, I knew I wanted to be a cellist years before I had a chance. I was, for example, prevented from starting by living in Burma, where there was only piano-teaching — and precious little of that.) But Hoffy was always generous. If I seriously over-shot my ability, he would take the music, very gently, from me and say, 'Some day you veel play this, pumpkin, and everyone veel cry.'

Which is not to say that Hoffy was not ambitious for me. Hoffy entered me in every local competition (several of which I actually won) and espoused my cause with the local, very accomplished, youth orchestra, the D C Youth Orchestra, where he organised the cellos. (We used to travel together to the run-down Washington high school where we rehearsed — mostly Mahler symphonies. Hoffy was not a fan of that school. He used to gloomily remark, 'Now vee descend to the coal mines', as we entered the building carrying our cellos.) I wound up the principal cello of the D C Youth Orchestra, playing on tours abroad and in the Kennedy Center and this experience absolutely cemented my already existing desire to 'be' John Martin, the ridiculously handsome principal cello of the National Symphony Orchestra.

Hoffy also (personally) introduced me to chamber music. I was perhaps all of fourteen when he picked me up in his BMW (Hoffy spent most of his disposable income on cars) and drove me — well, somewhere — and there I was, meeting three other Hoffys (all Jewish, all men, all considerably older than my own father). They were all also immensely kind to me, despite my lack of Jewishness, though one of them told me comfortingly, 'The nose is right!' (In musical circles I have often been believed to be Jewish, just thanks to my maternal grandfather's nose!)

Hoffy himself was still kinder, allowing me to play the first movement of Mozart's amazing quartet ('The Dissonance'), though he did swipe the still-more-beautiful second movement. That was my first experience of playing in a string quartet — my first experience, other than messing around playing duos with my gifted violist sister, of chamber music. I shall never forget it: the single tall light shedding just enough light on the music, the crackle of the real fire, the serious intensity of the Jews, the sound. I felt utterly intoxicated with the sound — as well as the communication. I don't believe I said a word as Hoffy drove me home, probably not even 'Thank you' (my manners were lousy) but my comfort is this: that with Hoffy one didn't always need words.

We were always extremely close: he was like the grandfather I'd never met (the one with the nose). Hoffy was annoyed when I went to music college, complaining on numerous occasions and in a blatantly accusatory tone, 'Now you are leaving me!' In fact, I'd been intensely loyal — possibly even too loyal. His only other professional-to-be cello pupil had left him to travel to Juilliard twice a month for her last two years — something for which I'm not sure Hoffy ever entirely forgave her. Her career has since exceeded mine in every particular — but then, it would probably always have done, as she was always the more gifted.

Hoffy taught and played quartets at background gigs into his eighties. I once asked him, 'What's the difference between playing professionally in your thirties and in your eighties?' Hoffy thought for a minute and then twinkled at me: 'About feefteen meenites varm-up!'

He suffered terrible depression when his wife died — though, having said that, they had yelled at each other a lot, as I'd always noticed! Yet they were intensely devoted all the same, and for a while my family and I worried that Hoffy might go into a decline. What perked him up was his lifelong love of Bridge, at which he was perilously accomplished. At some major Bridge competition or other, already aged about eighty-five, he met a comely widow of sixty-five and, less than a month later, married her. This turned out to be a disaster: she was after his money, and certainly got some of it. (This annoyed Hoffy no end, as money and the Democratic Party were almost as dear to him as music and Bridge.) As Hoffy said to me, with that rueful charm of his, 'There eess no fool like an old fool!' The truth was, Hoffy was born gregarious and adored company: he hated living in the house on his own. He was a born 'people person'.

However, in the end, even the seemingly immortal Hoffy got cancer. He called me the week before he died, sounding very depressed. ('I'd love to see you, pumpkin.') I arranged to come over the next week — but arrived just too late. My parents — who also loved him — attended his funeral without me.

It was a sad, strange visit, to come to McLean without seeing Hoffy, and I shall always regret not dropping everything to rush over the ocean. But, as my mother said, he knew how much I loved him, and how often I remember him, not just on 'Hoffy day', 6 December, but all the time, how I quote him to my students, how his studies — that thick, sure yet strangely elegant script — still lives on, how I still can hear the tones of his voice, in certain cello pieces, urging me to 'Suffer, baby, suffer!'

Of course, Hoffy was the expert on suffering, telling me once, rather ominously, 'I've got a thing or two to ask God'.

(I bet he has, too.)

Copyright © 12 December 2014 Alice McVeigh,

Kent UK

|